Project Info:

Reproduced with the permission of K. Ludvigsen, the former owner of the car

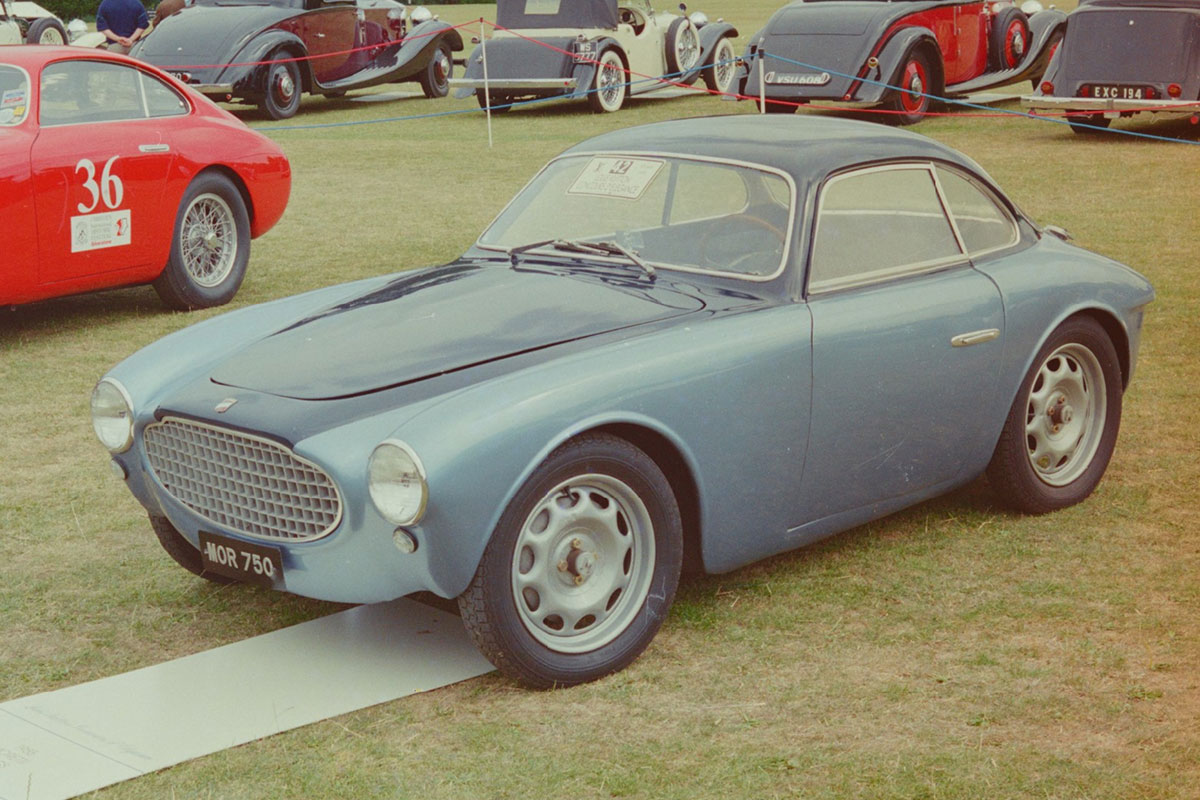

Having seen these charming coupes race at Watkins Glen and Columbus Air Force Base, I always had a soft spot for them. Thus I was alert when one was offered for sale in 1979. One of the coupes originally exported to California, it acquired a new grille there, an aluminium egg-crate design hand-crafted and signed by leading hot-rod artist and iconoclast Von Dutch. Ferrariesque, it resembles the grille of a 750 cc Berlinetta that competed in the Rallye Maroc in 1954.

First registered as being built in 1955, the coupe carried chassis number 1293. As explained to me by Giovanni’s son Segio, that meant that it was the 1,293rd car of all types that Moretti manufactured at its Turin factory since post-war production of four-cylinder cars began in 1948.

On the West Coast this Moretti made its way north to Washington state. By 1964 it was in Florida, the property of Norman and Betty Dobbins of Dunedin. In 1966 they sold it to Gene Cesari, a great enthusiast who put himself through university by importing and selling Bugattis in the 1950s.

Like the few who then owned this kind of Moretti, Gene’s dream was to restore it. He took the mechanical parts to a barn in Pennsylvania—acquiring a variety of other Moretti pieces over the years—and left the body and chassis with Jack O’Donnell in Westfield, New Jersey.

When I went to see the car in June, 1979 it was outdoors under multiple layers of canvas, blankets and plastic sheets. Its doors were missing, its seats a mere memory. But it was unmistakably a Moretti Berlinetta of the ilk I had so admired a quarter-century before. Thus began the saga of the restoration of this Moretti at the Ridgefield, Connecticut premises of Don and Mark Lefferts of Vintage Auto Restorations.

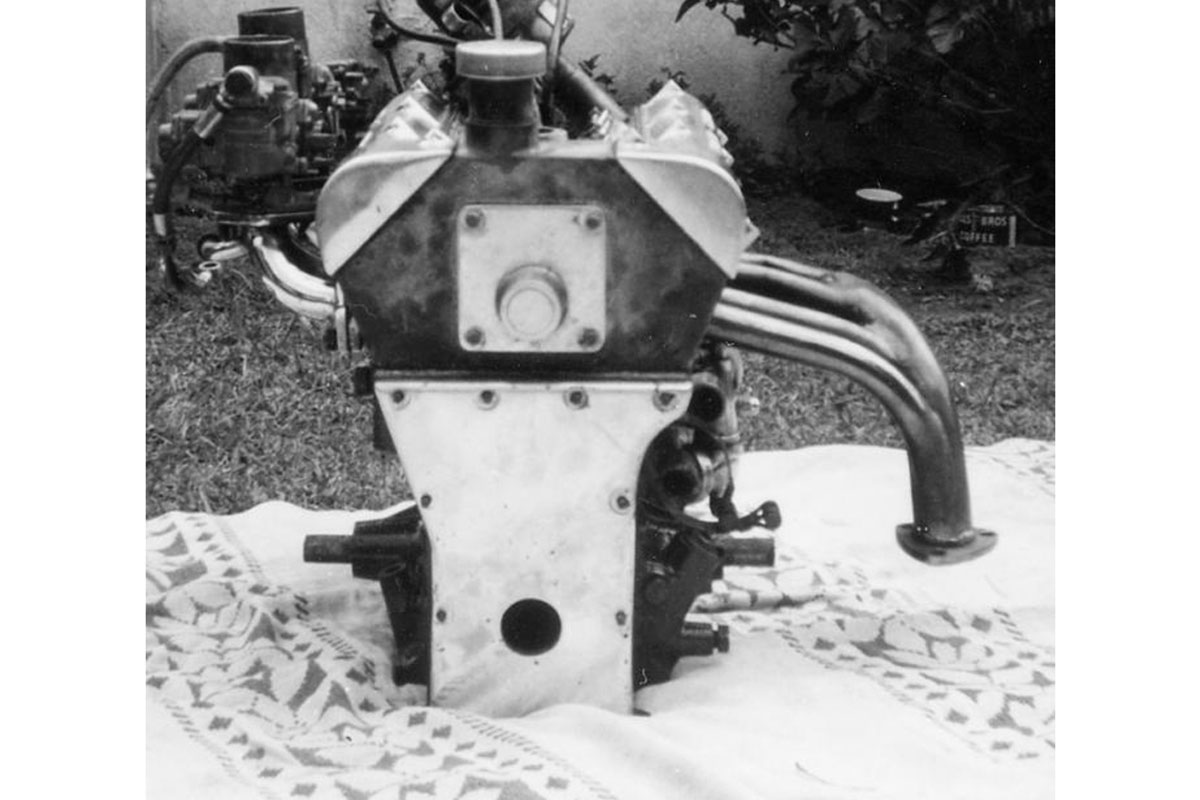

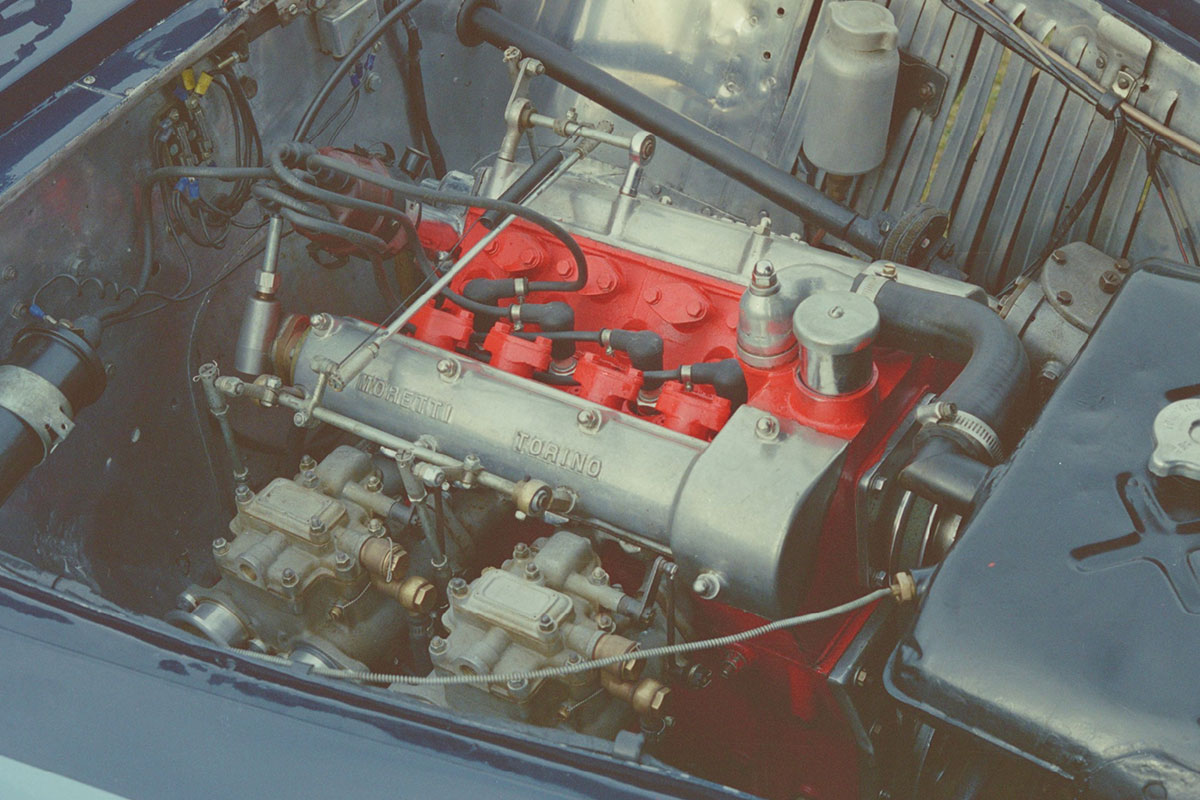

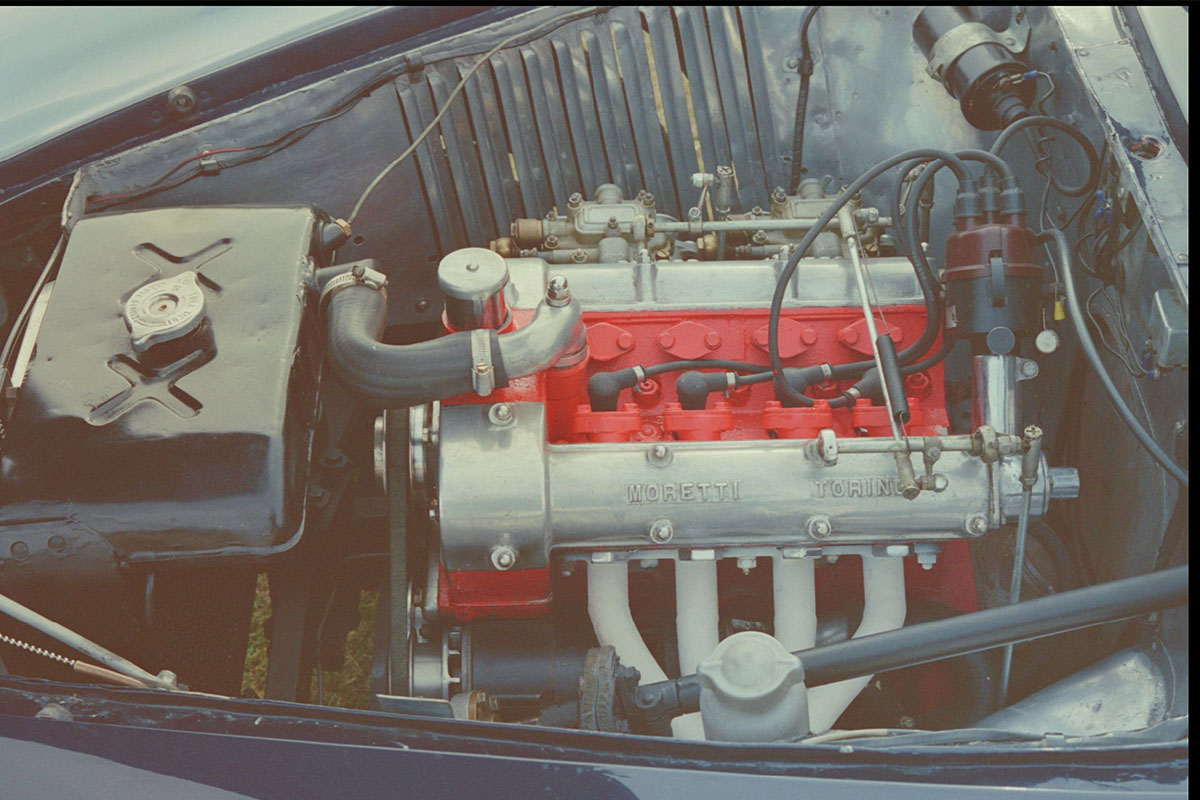

Their doubts about the quality of the three-bearing engine material led to my purchase from the factory of most of a five-main-bearing engine. Its rotating parts were not in good condition, however. I had help from Paul Morgan at Cosworth in getting a new crankshaft and connecting rods produced. Jahns pistons were sourced from California by the restorers.

The 1953-54 Morettis used downdraft Weber carburettors. We had no carburettors or manifold at all with either engine so this presented a major problem. A side-draft manifold from the cutaway display engine in the Moretti showroom was acquired and after extensive searches two early sand-cast Weber 42DCO3 carburettors were found, fitted and suitably choked and jetted. Throttle linkages and exhaust manifolds were made from scratch.

The resulting specification, with a lively 10.0 to 1 compression ratio, corresponded to that of 1955 when similar Moretti engines were rated at 71 bhp at 7,000 rpm. On the road it felt every bit that strong. And it sounded wonderful!

Although some Gran Sport Morettis had Borrani wire wheels, I was happy with the look of the ventilated 15-inch steel wheels on my car. They were fitted with 135SR15 Michelin ZX tyres.

The highly styled instruments are water temperature and oil pressure on the left of the column and speedometer, tachometer and fuel level on the right. The tachometer in this car was a Smiths chronometric, fitted in the States for racing and driven from the inlet camshaft.

Water temperature was a problem; even in traffic it didn’t always get warm enough! When the car came to Britain after a 10-year restoration in the US I entrusted it to talented New Zealander Don Fenwick, former chief of the Chequered Flag workshop. Don fitted an adjustable roller screen in front of the radiator much like the one on my former 1952 Maserati. With this I could keep the engine as warm as it liked to be.

When I first saw these Berlinettas in the 1950s I was beguiled by their low-backed seats. We found the right wide-wale corduroy to trim the seats, doors and tunnel to match the dark blue of the two-tone paint scheme—exactly the pattern originally used by Moretti. Light blue carpeting covered the floor and the rear deck, where the battery sat in an aluminium box and the spare wheel was tucked neatly into a cove.

Stepping down and into the Berlinetta is relatively easy through the wide and light doors. It’s cosy but by no means cramped, with adequate elbow room and a low central tunnel. Your shoulders are right at the window sills. When I bought the Moretti I had no idea whether I could fit into it; there is only just enough headroom. Yet somehow competitors managed to wear helmets in their Gran Sport Berlinettas.

The engine fires with a few pumps of the throttle pedal after a push on the aluminium starter button. Contrary to the reputation of Italian electrical systems, the Moretti starts reliably even in the rain. A lively clatter from the cams and followers rises above the engine’s busy buzz. With an ultra-light flywheel it revs fast at a prod of the throttle and stops just as fast.

The short, quick clutch sets the Berlinetta moving with a chirpy bounce. All four gears are useful; double-clutching engages first for the slowest city corners. To go up from second to third you just punch the lever forward in the compact gate.

Having seen these charming coupes race at Watkins Glen and Columbus Air Force Base, I always had a soft spot for them. Thus I was alert when one was offered for sale in 1979. One of the coupes originally exported to California, it acquired a new grille there, an aluminium egg-crate design hand-crafted and signed by leading hot-rod artist and iconoclast Von Dutch. Ferrariesque, it resembles the grille of a 750 cc Berlinetta that competed in the Rallye Maroc in 1954.

First registered as being built in 1955, the coupe carried chassis number 1293. As explained to me by Giovanni’s son Segio, that meant that it was the 1,293rd car of all types that Moretti manufactured at its Turin factory since post-war production of four-cylinder cars began in 1948.

On the West Coast this Moretti made its way north to Washington state. By 1964 it was in Florida, the property of Norman and Betty Dobbins of Dunedin. In 1966 they sold it to Gene Cesari, a great enthusiast who put himself through university by importing and selling Bugattis in the 1950s.

Like the few who then owned this kind of Moretti, Gene’s dream was to restore it. He took the mechanical parts to a barn in Pennsylvania—acquiring a variety of other Moretti pieces over the years—and left the body and chassis with Jack O’Donnell in Westfield, New Jersey.

When I went to see the car in June, 1979 it was outdoors under multiple layers of canvas, blankets and plastic sheets. Its doors were missing, its seats a mere memory. But it was unmistakably a Moretti Berlinetta of the ilk I had so admired a quarter-century before. Thus began the saga of the restoration of this Moretti at the Ridgefield, Connecticut premises of Don and Mark Lefferts of Vintage Auto Restorations.

Their doubts about the quality of the three-bearing engine material led to my purchase from the factory of most of a five-main-bearing engine. Its rotating parts were not in good condition, however. I had help from Paul Morgan at Cosworth in getting a new crankshaft and connecting rods produced. Jahns pistons were sourced from California by the restorers.

The 1953-54 Morettis used downdraft Weber carburettors. We had no carburettors or manifold at all with either engine so this presented a major problem. A side-draft manifold from the cutaway display engine in the Moretti showroom was acquired and after extensive searches two early sand-cast Weber 42DCO3 carburettors were found, fitted and suitably choked and jetted. Throttle linkages and exhaust manifolds were made from scratch.

The resulting specification, with a lively 10.0 to 1 compression ratio, corresponded to that of 1955 when similar Moretti engines were rated at 71 bhp at 7,000 rpm. On the road it felt every bit that strong. And it sounded wonderful!

Although some Gran Sport Morettis had Borrani wire wheels, I was happy with the look of the ventilated 15-inch steel wheels on my car. They were fitted with 135SR15 Michelin ZX tyres.

The highly styled instruments are water temperature and oil pressure on the left of the column and speedometer, tachometer and fuel level on the right. The tachometer in this car was a Smiths chronometric, fitted in the States for racing and driven from the inlet camshaft.

Water temperature was a problem; even in traffic it didn’t always get warm enough! When the car came to Britain after a 10-year restoration in the US I entrusted it to talented New Zealander Don Fenwick, former chief of the Chequered Flag workshop. Don fitted an adjustable roller screen in front of the radiator much like the one on my former 1952 Maserati. With this I could keep the engine as warm as it liked to be.

When I first saw these Berlinettas in the 1950s I was beguiled by their low-backed seats. We found the right wide-wale corduroy to trim the seats, doors and tunnel to match the dark blue of the two-tone paint scheme—exactly the pattern originally used by Moretti. Light blue carpeting covered the floor and the rear deck, where the battery sat in an aluminium box and the spare wheel was tucked neatly into a cove.

Stepping down and into the Berlinetta is relatively easy through the wide and light doors. It’s cosy but by no means cramped, with adequate elbow room and a low central tunnel. Your shoulders are right at the window sills. When I bought the Moretti I had no idea whether I could fit into it; there is only just enough headroom. Yet somehow competitors managed to wear helmets in their Gran Sport Berlinettas.

The engine fires with a few pumps of the throttle pedal after a push on the aluminium starter button. Contrary to the reputation of Italian electrical systems, the Moretti starts reliably even in the rain. A lively clatter from the cams and followers rises above the engine’s busy buzz. With an ultra-light flywheel it revs fast at a prod of the throttle and stops just as fast.

The short, quick clutch sets the Berlinetta moving with a chirpy bounce. All four gears are useful; double-clutching engages first for the slowest city corners. To go up from second to third you just punch the lever forward in the compact gate.

With a throaty rasp the three-quarter-litre engine thrusts the little car forward, easily up to 3,000 rpm and thereafter with convincing force. Surprised to find its speedometer reading slow instead of fast, Road & Track found it took 15.5 seconds to 60 mph and 28.2 to 80. Theirs reached 69 mph at 7,000 rpm in third gear. Mine, in a higher state of tune, surged fast to 6,000+ and at 80 mph still leapt forward when the throttle was pressed down.

Negligible wheel travel keeps the Berlinetta glued to every bump in the road. After fine-tuning of the special Spax dampers we had made for the car its ride became acceptable wherever its ground clearance let it go.

Road & Track didn’t like the Moretti’s steering very much and neither did I. It’s too vague around centre position and it demands more effort that it should in hard cornering. We went through all the tie-rod ends and replaced the bearings in the steering box so it was as good as we could make it.

Considering its abbreviated wheelbase the Moretti felt dead steady in corners and inspired great confidence. With its wide track and stiff springing in front it understeers strongly. Attention to tyre pressures helped both steering and handling.

It was a tremendous thrill for me to commence driving the Moretti on the roads of Britain. She enjoyed her outings, in 1988 and 1990 taking part in the RAC’s Norwich Union Classic Run and later in a Haynes Two-Day Classic. Annette and I even arrived in it at Glyndebourne in black tie for the opera. Unfortunately they have more than a few sleeping policemen!

Restored to vivid life, perhaps at that time the only running example of its kind in the world, in the 1980s this Moretti 750 Gran Sport Berlinetta began getting the recognition it deserved. In 1987, before the restoration was complete, in the Concours d’Elegance at the Lime Rock Fall Festival it was awarded first-place prize in the Postwar Foreign Sports class. It was a featured car in the International Classic and Sportscar Show at Britain’s National Exhibition Centre in May 1990.

At the highest level of design appreciation and assessment, the Moretti was applauded by the Louis Vuitton Concours d’Elegance. She so bewitched the judges at the Stowe 1990 Louis Vuitton meeting that they issued a special invitation to the Concours at Parc Bagatelle in Paris. Subsequently she appeared in the Louis Vuitton Concours at the Goodwood Festival of Speed. Publications in Britain, America, Italy and Japan gave space to this car and the Moretti story.

Various problems led me to commission a rebuild of the engine which was carried out during 1991 in Calne, Wiltshire by Nelson Engine Services. When in 1997 the RAC decided to organise a classic-car run from York to Scotland to celebrate its centenary, we decided to take part. Amidst all the Bentleys, Alvises and Jaguars the Moretti cut an exotic figure with her rasping exhaust gaining her the ‘bumblebee’ nickname.

This was a long drive, including our initial trip up from London. The Moretti mastered it in good form apart from an erratic dynamo on the drive home. We managed it too, complete with luggage, which made us wonder whether the Mille Miglia—hitherto thought beyond the capabilities of the car and its occupants—could be on the cards. We put in an entry for 1998 and were accepted.

Early in 1998, confident in our car, we took part in a Haynes two-day run to Wales. Soon we realised that the voltage regulator wasn’t playing ball. There were other problems, so we instructed the breakdown truck to take her directly to Tony Merrick’s workshop near Reading in Berkshire. We asked Tony to go through her in preparation for the Mille Miglia. This he did with his usual thoroughness, even armouring the silencer’s vulnerable underside.

Collecting the Moretti in Brescia, where she was decanted from a van with the cars of other Merrick customers, Annette and I set out on the demanding route with no support whatsoever. To our great relief the 750 Gran Sport performed like a champ. Only one stop was needed to free a clutch pedal that didn’t want to return. Our biggest problem was finding room inside the car for all the goodies thrust upon us at every check point.

We had really tackled the Mille Miglia for the Moretti’s benefit, taking her back home for a visit after a long stay away. At one stop a gentleman bent low to have a word. ‘You know,’ he said, ‘we are so glad that you have brought this car here. They are very rare in Italy because most of them were exported so we never see them. Thank you!’ That alone was worth the trip.

We parted from the Moretti in 2001, selling her at auction to a Connecticut collector who had her primped in depth in Italy under the guidance of Adolfo Orsi. In the meantime Morettis of all descriptions began emerging from the woodwork around the globe, carrying the flag for this little-known marque. I was proud and pleased to have led a revival of interest in the doughty motor maker who effloresced so brightly and briefly in the shadow of Turin’s mighty Fiat.

Negligible wheel travel keeps the Berlinetta glued to every bump in the road. After fine-tuning of the special Spax dampers we had made for the car its ride became acceptable wherever its ground clearance let it go.

Road & Track didn’t like the Moretti’s steering very much and neither did I. It’s too vague around centre position and it demands more effort that it should in hard cornering. We went through all the tie-rod ends and replaced the bearings in the steering box so it was as good as we could make it.

Considering its abbreviated wheelbase the Moretti felt dead steady in corners and inspired great confidence. With its wide track and stiff springing in front it understeers strongly. Attention to tyre pressures helped both steering and handling.

It was a tremendous thrill for me to commence driving the Moretti on the roads of Britain. She enjoyed her outings, in 1988 and 1990 taking part in the RAC’s Norwich Union Classic Run and later in a Haynes Two-Day Classic. Annette and I even arrived in it at Glyndebourne in black tie for the opera. Unfortunately they have more than a few sleeping policemen!

Restored to vivid life, perhaps at that time the only running example of its kind in the world, in the 1980s this Moretti 750 Gran Sport Berlinetta began getting the recognition it deserved. In 1987, before the restoration was complete, in the Concours d’Elegance at the Lime Rock Fall Festival it was awarded first-place prize in the Postwar Foreign Sports class. It was a featured car in the International Classic and Sportscar Show at Britain’s National Exhibition Centre in May 1990.

At the highest level of design appreciation and assessment, the Moretti was applauded by the Louis Vuitton Concours d’Elegance. She so bewitched the judges at the Stowe 1990 Louis Vuitton meeting that they issued a special invitation to the Concours at Parc Bagatelle in Paris. Subsequently she appeared in the Louis Vuitton Concours at the Goodwood Festival of Speed. Publications in Britain, America, Italy and Japan gave space to this car and the Moretti story.

Various problems led me to commission a rebuild of the engine which was carried out during 1991 in Calne, Wiltshire by Nelson Engine Services. When in 1997 the RAC decided to organise a classic-car run from York to Scotland to celebrate its centenary, we decided to take part. Amidst all the Bentleys, Alvises and Jaguars the Moretti cut an exotic figure with her rasping exhaust gaining her the ‘bumblebee’ nickname.

This was a long drive, including our initial trip up from London. The Moretti mastered it in good form apart from an erratic dynamo on the drive home. We managed it too, complete with luggage, which made us wonder whether the Mille Miglia—hitherto thought beyond the capabilities of the car and its occupants—could be on the cards. We put in an entry for 1998 and were accepted.

Early in 1998, confident in our car, we took part in a Haynes two-day run to Wales. Soon we realised that the voltage regulator wasn’t playing ball. There were other problems, so we instructed the breakdown truck to take her directly to Tony Merrick’s workshop near Reading in Berkshire. We asked Tony to go through her in preparation for the Mille Miglia. This he did with his usual thoroughness, even armouring the silencer’s vulnerable underside.

Collecting the Moretti in Brescia, where she was decanted from a van with the cars of other Merrick customers, Annette and I set out on the demanding route with no support whatsoever. To our great relief the 750 Gran Sport performed like a champ. Only one stop was needed to free a clutch pedal that didn’t want to return. Our biggest problem was finding room inside the car for all the goodies thrust upon us at every check point.

We had really tackled the Mille Miglia for the Moretti’s benefit, taking her back home for a visit after a long stay away. At one stop a gentleman bent low to have a word. ‘You know,’ he said, ‘we are so glad that you have brought this car here. They are very rare in Italy because most of them were exported so we never see them. Thank you!’ That alone was worth the trip.

We parted from the Moretti in 2001, selling her at auction to a Connecticut collector who had her primped in depth in Italy under the guidance of Adolfo Orsi. In the meantime Morettis of all descriptions began emerging from the woodwork around the globe, carrying the flag for this little-known marque. I was proud and pleased to have led a revival of interest in the doughty motor maker who effloresced so brightly and briefly in the shadow of Turin’s mighty Fiat.

K. Ludvigsen 2001